DAVID CLARKE ponders the origins of the phantom bowmen imagined by two fantasy authors at the outbreak of the First World War

They were like men who drew the bow, and with another shout, their cloud of arrows flew singing and tingling through the air towards the German host…the singing arrows darkened the air; the heathen horde melted from before them.

Arthur Machen, The Bowmen, September 1914

….our giant minds…defend us, sending out legions of imaginary warriors to materialise before the mind's eye of the foe. They see them – they see their bows drawn back – they see their slender arrows speed with unerring precision toward their hearts. And they die – killed by the power of suggestion.

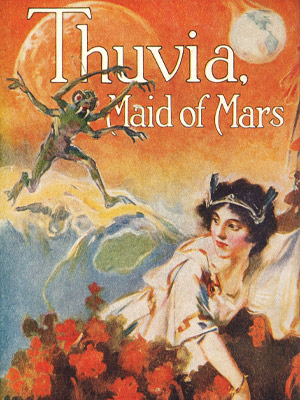

Edgar Rice Burroughs, Thuvia: Maid of Mars, 1916

One hundred years ago the great European powers were drawn into the first war to be fought on a truly global scale. Four years of conflict produced an outpouring of literature and art, and many caught up in the carnage found sustenance in religion and other types of supernatural belief. There were national calls to prayer and the notion of 'God With Us' encouraged the idea that troops had divine protection. Others reverted to what Paul Fussell has called "a mediæval mindset" that encouraged belief in a variety of apocalyptic prophecies, superstitions, wonders, miracles, rumours and legends.1 The greatest legend of the war, The Angels of Mons, emerged from the first battle fought by British troops in Europe since Wellington's forces defeated Napoleon at Waterloo a century earlier (see FT170:30-38). At the time, the Belgian battle had a symbolic importance that far outweighed any strategic significance. For the British Army, World War I ended where it began, with the first and last English soldiers both killed on the outskirts of Mons in 1914 and 1918.2

On the morning of 23 August 1914, the professional soldiers of the small but well trained British Expeditionary Force collided with the advancing German army along the Mons-Conde canal. The BEF were heavily outnumbered, but they managed to hold back the German First Army long enough to allow their French allies to regroup on the Marne and save Paris. The retreat from Mons inspired the Welsh-born author of fantasy fiction, Arthur Machen, to write The Bowmen. He dismissed his short story as an "indifferent work", but spent the remainder of his life insisting it was the genesis of the Angels of Mons. His protests made little impression upon those who came to believe that real angels had intervened on the Allied side, not only at Mons but elsewhere in the war.

Why was he disbelieved? The ferocity of the battles that followed the retreat and their uncertain outcome encouraged an expectant atmosphere on the Home Front that was receptive to all kinds of supernatural ideas. During 1915, rumours spread that Machen had been tipped off by a military source, or that the idea for The Bowmen had been placed in his hand by 'a lady in waiting' sent by a highly-placed source in the British Royal family. There was also Harold Begbie's theory that Machen had received a telepathic impression of 'the vision' from the brain of a dying soldier on the battlefield3

Speculation about Machen's source has continued to the present day. In 1992, Kevin McClure wrote in Visions of Angels and Bowmen that Machen's explanation was "not the whole story" and "the men of the BEF, or a number of them, anyway, were aware of reports of a cloud or of angels before the publication of The Bowmen"4. But was that really the case? In The Bowmen and Other Legends of the War Machen provides a clear account of his inspiration. It took one week for news of the battle of Mons to reach London. On his way to Mass on the morning of Sunday, 30 August 1914, he saw billboards that told of heavy losses and the desperate need for reinforcements at the Front. As the priest sang and incense drifted above his gospel book, he saw: "…a furnace of torment and death and agony and terror seven times heated, and in the midst of the burning was the British Army". During the ritual he imagined the archers who fought for Henry V at Agincourt invoking the Celtic saints for protection. Thinking of the BEF, he saw "our men with a shining about them".

In writing The Bowmen, Machen admitted he dipped into a deep well of legend and myth that stretched far beyond Agincourt. His story drew upon a range of sources, from Herotodus's account of supernatural intervention in the Persian Wars to Kipling's Lost Legion. In The Bowmen a "Latin scholar" amongst the BEF is encouraged when he sees an image of St George before they leave England. During the retreat from Mons he calls out Adsit Anglis Sanctus Georgius (St George help the English!) in desperation when his pals are cut off and face imminent death. Suddenly "a shudder and an electric shock" pass through his body and the roar of battle dies down. A chorus of voices cry out "St George! St George!" and a long line of "men who drew the bow" appear beyond the trenches to rain arrows on the advancing German infantry. As the enemy soldiers crash to the ground, he knows "St George had brought his Agincourt bowmen to help the English".

Whether by accident or design, the editor of the Evening News published The Bowmen on 29 September 1914, the feast day of the archangel Michael. In Victorian art and iconography, St George and St Michael were interchangeable. Both appeared as shining warrior angels that protected Christian soldiers and slew dragons. The clincher for those who knew was the reference to "a long line of shapes with a shining about them". In 1915 Machen wrote that "in the popular view shining and benevolent supernatural beings are angels and nothing else and so, I believe, the Bowmen of my story have become 'the Angels of Mons'."5

During my research for my book The Angel of Mons (2004) I was unable to locate a single reliable eye-witness account of a vision of either bowmen or angels that could be confidently dated before The Bowmen. But one odd literary coincidence has led me to reconsider whether Machen's imagination really was the only source for the vision of phantom bowmen. Before he gained employment as a journalist, Machen was fond of exploring the slippery boundary between fact and fiction, but he was not the only wordsmith to produce tales of magical armies from the cauldron of war. During the summer of 1914, as Europe stood on the brink of World War I, the creator of Tarzan, Edgar Rice Burroughs, was at work in Chicago expanding his trilogy of Martian novels. In his first story, A Princess of Mars, former Confederate soldier John Carter is transported by astral projection to the red planet where he is drawn into a series of magical adventures. Mars is known as Barsoom to its warring tribes and the alien warlords and creatures he meets mirror those from ancient mythology.6 The fourth novel in the Martian cycle, Thuvia, Maid of Mars, appeared in 1916 and The Phantom Bowmen of Lothar appear in chapter seven. The Lotharians are an ancient race who have become trapped in their city surrounded by mountains. The few remaining Lotharians have developed extraordinary psychic powers to defend their isolated city from attacks by hordes of green barbarians, the Torquasians.

When the Torquasians lay siege to Lothar they encounter the bowmen, "a fantastic army of mentally projected phantoms created by the sheer willpower of the few living Lotharians". Richard Lupoff's biography of Burroughs describes the bowmen as being so realistic that "a vast number of casualties are inflicted on the Torquasians… and the green men are repeatedly driven off."7 His 1976 study of the Martian cycle makes the link between the bowman of Lothar and The Bowmen of Mons and drops a bombshell: Burroughs' notebooks show that Thuvia, Maid of Mars, was written between April and June 1914.8 According to Irwin Porges, Burroughs completed the story during a furious writing schedule that took him from California to New York during the summer of 1914.9 The finished typescript was sent to his editor at All-Story Weekly soon after 20 June. If these dates are accurate, his story was completed at least two months before Machen's fantasy was inspired by news of the BEF's stand at Mons. Lupoff maintains "there was no possible way for Burroughs to have read Machen's story before writing his own tale or vice versa." If this was a coincidence, it was "one of the most remarkable such in modern literature."10 Did the idea for phantom bowmen at Mons and on Mars occur independently to two authors separated by the Atlantic Ocean? If so, this may be an example of literary synchronicity: an idea that was visualised simultaneously by two powerful minds during the world crisis. The concept of synchronicity was first described by Carl Jung who, in fact, refers to the Angels of Mons in his 1958 book Flying Saucers as "a visionary rumour". Perhaps the two ideas were, as Jung opined, examples of a type of rumour that was told in different parts of the world "but differs from an ordinary rumour in that it is expressed in the form of visions, or perhaps owed its existence to them in the first place and is kept alive by them".

NOTES

1. Paul Fussell, The Great War in Modern Memory (OUP 1975)

2. Private John Parr of the Middlesex Regiment died at Obourg, near Mons, on 21 August 1914. He was 15 or 16 and had lied about his age on enlistment. George Ellison, 40, of the 5th Royal Irish Lancers, died nearby one and a half hours before the Armistice was declared on 11 November 1918. His grave in the St Symphorien military cemetery faces that of Parr.

3. See my book The Angel of Mons (Wiley 2004) for a full discussion of Machen's sources and his clashes with those who believed in divine intervention such as Harold Begbie, author of On The Side of the Angels (1915).

4. Kevin McClure, Visions of Bowmen and Angels (Harrogate, 1992).

5. Arthur Machen, The Bowmen and Other Legends of the War (London 1915).

6. The first Barsoom story was serialised as Under the Moons of Mars in the pulp magazine The All-Story during 1912. It appeared as a novel in 1917.

7. Richard A Lupoff, Edgar Rice Burroughs: Master of Adventure (Canaveral Press, 1965).

8. Richard A Lupoff, Barsoom: Edgar Rice Burroughs and the Martian Vision (Mirage Press, 1976).

9. Irwin Porges, Edgar Rice Burroughs (Brigham Young University Press, 1975).

10. I am grateful to Thomas Miller and Alan Bundy, members of Caermaen, the newsgroup of the Friends of Arthur Machen, for drawing my attention to Lupoff's biography of ERB.

DAVID CLARKE is a regular columnist and contributor to Fortean Times. His latest book is Britain's X-traordinary Files, published by Bloomsbury on 25 September; it includes a chapter covering The Angels of Mons and other legends of World War I.

For more strange news, fortean features and expert columns every month try Fortean Times magazine today with 3 issues for just £1.